[The Weekend Bulletin] #141: Capital Cycles, Portfolio Management, Thematic Expertise, Linearity Bias, ...

...Odds of a Good Investment, Yesterday is Defined by Today, Leadership Lessons from an Orchestra, Buffett on Moats, and more.

A digest of some interesting reading material from around the world-wide-web. Your weekly dose of multi-disciplinary reading.

Investing Wisdom

I thoroughly enjoyed listening to this conversation of Russell Napier & Jeremy Hosking with podcast host Stephen Clapham. Russell is a global macro consultant and was earlier the Asia strategist at CLSA. Jeremy is a partner of Hosking Partners and was previously a founding partner of Marathon Asset Management in London. He is a co-author of the cult book Capital Account and its sequel Capital Returns. The conversation primarily revolves around the capital cycle and it's application in investing. Although, in order to explain the concept, the conversation does digress in to current macro and market conditions, but the views are interesting and different.

Here is a very good thread covering two important portfolio management principles: minimizing correlation and rebalancing intelligently.

Nick Maggiulli revisits some of his past investment mistakes in the current context to emphasize the importance of process over outcome and how the present defines the past. How we view yesterday is determined by what is happening today, he explains.

One of the ways in which we can reduce our investment regrets is by basing our decisions not on narratives or the past, but on probabilities. A good investment in one in which the odds are in our favor, although calculating odds doesn’t come intuitively to us. This article helps.

This short article makes two very interesting observations: a) having a thematic flavor helps a fund outperform; b) fund managers with specific expertise in their educational backgrounds do well managing thematic funds in their area of expertise. Read on to know why.

The following is a well-rounded perspective from Buffett on competitive advantage or moats (courtesy: Frederik Gieschen):

"I’ve never really read Porter. I’ve read enough about him to know that we think alike, in a general way. I think he talks about durable or sustainable competitive advantage and that is exactly the way we think"

"The best way to do it is study the people that have achieved that and ask yourself how they did it and why they did it."

"What it is that gives you that moat around the razor blade business? Here’s a worldwide business and yet people don’t go into it.

Why was State Farm successful against people that had lots of capital? We like to ask ourselves questions like that."

"Study things like Mrs. B out at the Nebraska Furniture Mart, who takes $500 and turns it into the largest home furnishing store in the world. There has to be some lessons in things like that. What gives you that kind of a result and that kind of competitive advantage over time?"

"That is the key to investing. If you can spot it when others don’t spot it so well, you will do very well. And we focus on that."

Mental Models & Behavioral Biases

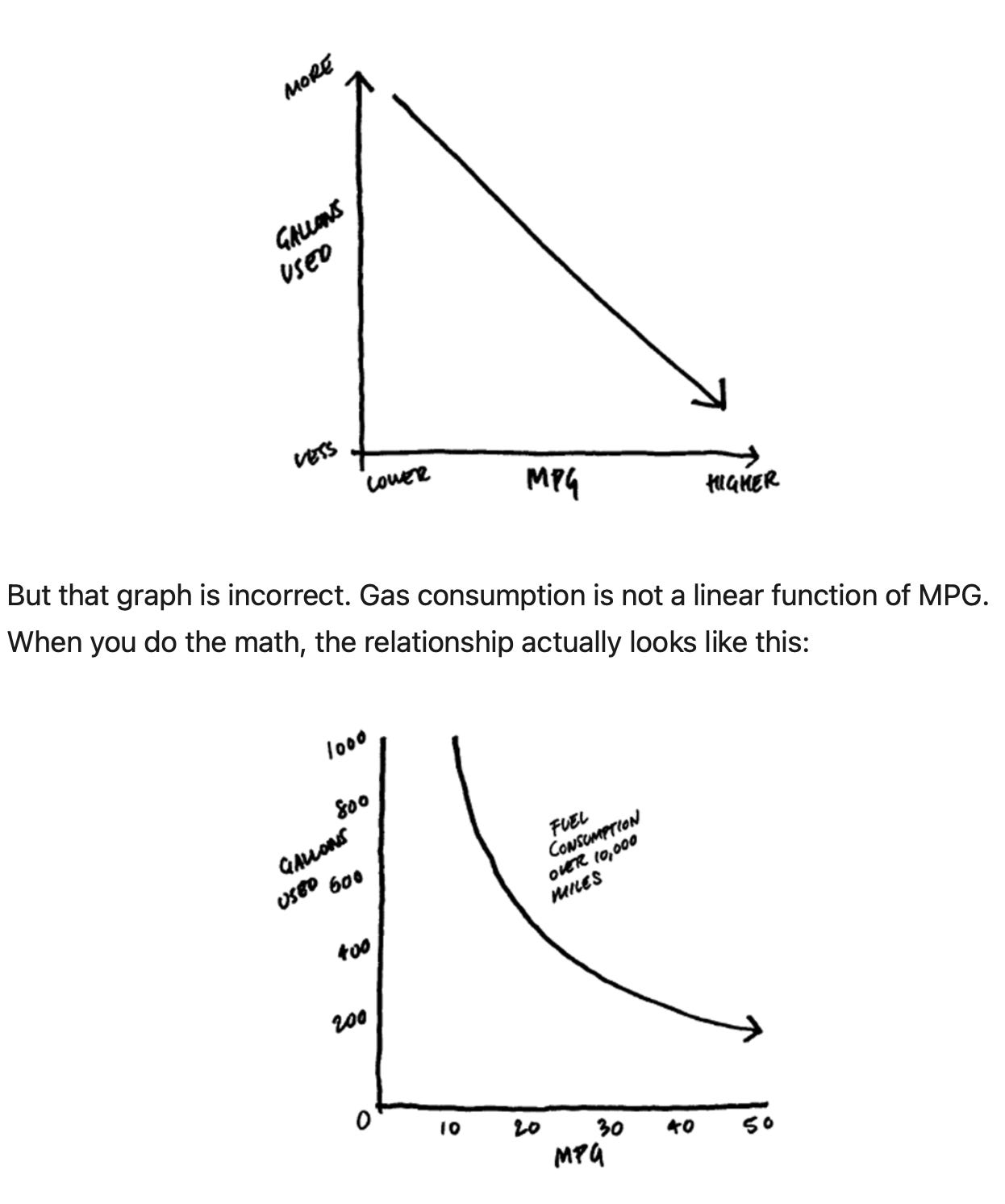

We often look at things simplistically - in a linear manner, observing only the first order impacts. However, a lot of things in life, like investing, are non-linear. For such non-linear or complex systems, it is important that we consider not just the first order impacts but also the second order consequences. Take the case of inflation - should we celebrate cost cutting measures to protect margins - are they sustainable for the long term? What about pricing power - is taking a 5-8% price hike in a year as easy as a 2-3% hike every year? For how long can you keep increasing prices before the customers start looking at alternatives? These and other important questions are raised in this post that asks us to be beware of linearity bias.

The above discussion reminded of this problem from an old HBR article:

Personal Development

In this very entertaining and educative talk, the speaker spells out some useful leadership lessons drawn from the way conductors conduct their orchestras.

One of the most common retirement advice is to build multiple income streams. While most of us are usually clueless as to how, there are some who are blessed with the knack of making money. Here is one such story involving actor Ryan Reynolds (who has many such successes) and the world's third-oldest football club.

Blast From The Past

Revisiting articles from a past issue for the benefits of refreshing memory and spaced repetition, as well as for a fresh perspective. Below are articles from #67:

Here is a quantitative rumination on Warren Buffett's quip that its far better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price, rather than a fair business at a wonderful price. While we all have some idea of what a wonderful business is like, there is no readily available deduction of a 'fair price' - a subjective assessment hitherto. This thread provides a way to mathematically deduce the fair price of a business. If you've always worried about what the right multiple to value a business is, you'll find a simple way to arrive at that multiple in it.

This interview (page 29 onwards) spotlights the journey, investment philosophy, and ideas of John Huber of Saber Capital. For those of you not familiar, John is a not only a good investor (he brings interesting perspectives to well known businesses) but also a great writer (his prices on ROIC and moats make for great reads). This interview makes for a good peak into the mind of great investment thinker. Below are some snippets:

"There are two main categories of investments that I think my portfolio has had over time. One is what I call dominant moats. These are really durable, high-quality, strong businesses with great balance sheets and very entrenched business models. They also tend to be mature...Then the second category are what I call emerging moats, and these are the compounders. These are the companies that have really high returns on capital, long growth runways, and are developing a strong lead."

"When I first invested in Apple in 2016, it had a valuation of around $500 billion. In two years, it went to a trillion. Then inside of three months, in late 2018, it went down 40%, shedding about $400 billion in value in just one quarter. Then from there, it went back to $1.5 trillion in just a year, up 150% from $600 billion. All of this was before COVID. It just goes to show you how the largest, most well-followed stock in the world can fluctuate far more significantly than the underlying value of the business. Why is that the case? Why is there an opportunity with Apple? I think one reason is time horizon –some people didn't want to own Apple because they were worried about the next quarter."

"I think there was also an analytical edge with Apple; this refers to looking at things through a different lens than others. In this case, I think some people were looking at Apple like a computer hardware company. A computer hardware company sells a commoditized product, margins will revert to the mean over time, and any excess returns on capital will be fleeting. They'll revert to the mean, and you'll never produce any excess profitability.

The other way to look at Apple was to view it as a consumer brand, along the lines of a Starbucks or a Nike. Nike makes a product from commodity inputs, manufactured overseas. Most of their products are essentially replicable commodities, but they get a 75% markup over their costs to make those products, and those gross margins exist because of the brand that Nike has.

...I think the combination of short term time horizons and thinking about Apple in a different way created an environment that resulted in a stock that was significantly undervalued, even though it was the most widely followed company in the market."

"Opportunity cost is a big factor in investing. Sometimes you make a mistake when you buy a stock, but the most costly mistakes can be when you sell something that you should have kept, because the opportunity cost of forgone profits can grow to become many times the size of a loss incurred by making a bad investment."

"I'm a conservative investor by nature, but there are drawbacks to being too conservative. I just read a note by my friend, Rob Vinall who runs a firm called RV Capital. He made a great point – banks that are aggressive when underwriting loans end up going bust, but so do banks that are too conservative over time, because they’ll miss writing the loans that are most profitable, which is needed to pay for the inevitable mistakes. As investors, our goal should be accuracy when evaluating a business."

This is a hilariously honest read. It addresses one of the biggest decisions of our lives, one of the real long term choices that we make - marriage. It posits that we are all going to marry the wrong person. No matter how much diligence we conduct, choosing whom to commit ourselves to is merely a case of identifying which particular variety of suffering we would most like to sacrifice ourselves for. Hidden behind this matrimonial column is the secret elixir to a happy life (married or otherwise): "We should learn to accommodate ourselves to “wrongness,” striving always to adopt a more forgiving, humorous and kindly perspective".

Readworthy Passage

Let's read together a random, but read-worthy, passage from a randomly picked book.

In fairness, we should acknowledge that some acquisition records have been dazzling. Two major categories stand out.

The first involves companies that, through design or accident, have purchased only businesses that are particularly well adapted to an inflationary environment. Such favored business must have two characteristics: (1) an ability to increase prices rather easily (even when product demand is flat and capacity is not fully utilized) without fear of significant loss of either market share or unit volume, and (2) an ability to accommodate large dollar volume in- creases in business (often produced more by inflation than by real growth) with only minor additional investment of capital. Managers of ordinary ability, focusing solely on acquisition possibilities meeting these tests, have achieved excellent results in recent decades. However, very few enterprises possess both characteristics, and competition to buy those that do has now become fierce to the point of being self-defeating.

The second category involves the managerial superstars-men who can recognize that rare prince who is disguised as a toad, and who have managerial abilities that enable them to peel away the disguise. We salute such managers as Ben Heineman at Northwest Industries, Henry Singleton at Teledyne, Erwin Zaban at National Service Industries, and especially Tom Murphy at Capital Cities Communications (a real managerial "twofer", whose acquisition efforts have been properly focused in Category 1 and whose operating talents also make him a leader of Category 2). From both direct and vicarious experience, we recognize the difficulty and rarity of these executives' achievements. (So do they; these champs have made very few deals in recent years, and often have found repurchase of their own shares to be the most sensible employment of corporate capital.)

Your Chairman, unfortunately, does not qualify for Category 2. And, despite a reasonably good understanding of the economic factors compelling concentration in Category 1, our actual acquisi- tion activity in that category has been sporadic and inadequate. Our preaching was better than our performance. (We neglected the Noah principle: predicting rain doesn't count, building arks does.)

- From THE ESSAYS OF WARREN BUFFETT by Lawrence A. Cunningham

Quotable Quotes

"Much of the real world is controlled as much by the ‘tails’ of distributions as by averages: by the exceptional, not the mean; by the catastrophe, not the steady drip; by the very rich, not the “middle class.” We need to free ourselves from ‘average’ thinking."

“To attain knowledge, add things every day.

To attain wisdom, remove things every day.”

- Lao Tzu

* * *

That's it for this weekend folks.

Have a wonderful week ahead!!

- Tejas Gutka

[Nov 05, 2022]

Marvelous collection.